Do we need to pop the bubble?

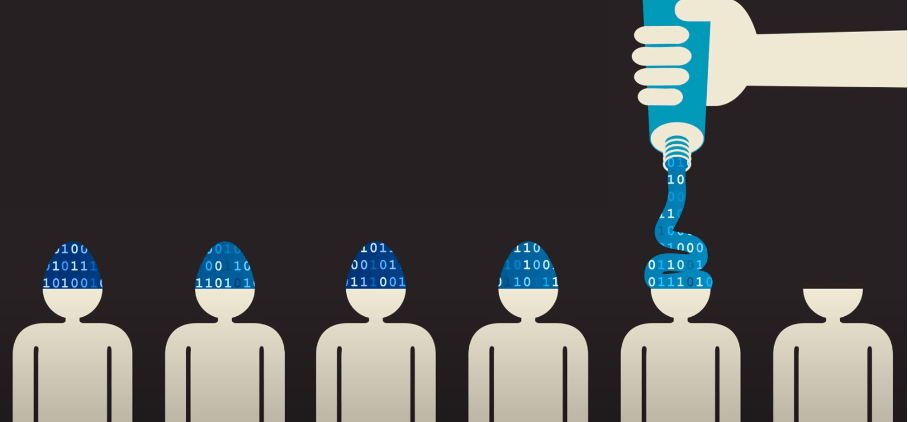

Machine learning is particularly interesting where large amounts of data need to be evaluated. Data is accumulating pretty much everywhere: While jogging via a fitness app, from surveillance cameras that focus on us on each of our movement, and from the mobile phone that we carry which us around and which dutifully reports to every cell tower we pass. Ultimately there is all the data derived from the “Internet of Things”, physical objects that are connected and exchange data with other devices. Machine learning algorithms allow us to find patterns in all these data and allow to make predictions about what is going on in the world and how people, trends, processes, and much more could develop in the future. The data from our digital profile – or better – the algorithm makes digital profile from our data and makes predictions about our behaviour and interests. This can be extremely useful for the advertisement industry since it enables them to make specific suggestions that are meant to fit exactly to our taste. Andres Lewis says: “If you’re not paying for something, you’re not the customer; you’re the product being sold”. Furthermore, algorithms sort some content, and prevent users of drowning in an overabundance of data. Thus, algorithms can influence what part of the world we see on Google or Instagram, for example. However, through this sorting out of the algorithms, we only get to see what fits our data profile. This raises the question of what this means for our society. Are we trapped in our algorithm filter bubbles and thus mentally limited?

According to the internet activist Eli Pariser [1], who coined the term “filter bubble” in his book of the same name, such bubbles are created because websites try to algorithmically predict what information the user wants to find. Pariser finds it problematic that you have no direct influence on the way information is filtered for you. He finds this particularly questionable regarding political decisions According to his thesis, this means that if someone searches for an article on a certain topic via Google, for example, only articles that fit the specific profile will be suggested to this person. Thus, it happens that depending on the user, other realities are created. Are we moving more and more in a direction that we put our needs, opinions, and attitudes in the hands of algorithms?

What role do algorithms play in the formation of individual opinions? This question is not so easy to explain. A non-representative study by Jacob Weisberg (2011) with a sample size of five people showed that the Google search results of people with different political attitudes were almost identical. A more extensive study by the organization Algorithm Watch (2017) analyzed three million records from donated data in Google searches. There were some regional, but not specifically political, differences between the results. However, a small number of individuals received significant variations from the others. Martin Deuz and Matthew Fuller (2011) found significant differences of searching results in their study. However, their research is aimed at showing users appropriate products and advertisements rather than instilling in them a specific worldview. More problematic than search engines, however, are social media. Since social media, any person with Internet access and an account on a social media platform has the opportunity, to address several million people with his or her statement. And there is no editorial team, which proves if this information is right or not. Moreover, the operators on social media platforms have a great interest in showing users what interests them most or on which information they want to pay attention and spend therefore much time on the platforms.

Filter bubbles are, to a large extent, less destiny/fate than convenience. In regard of political attitudes, they are not a new phenomenon. Even by choosing a particular newspaper, one’s political attitudes tend to be confirmed or not. As the internet is full of data, therefore a certain pre-sorting of the research results is always needed and important.

However, it is to a large extend the user’s responsibility to obtain information diversely and from reliable sources. Search engines just provides you a certain probability for an answer – in the end you always must give the answer to yourself. The division of society is therefore not caused by filter bubbles but by the way people use media to get their information. The fear of a separation of society through these algorithmically determined filter bubbles is probably not entirely justified. Nevertheless, the rankings of the answers, and therefore the influences of a certain information filtering, especially through social media, should not be underestimated.

Again, it’s you – you have to pose the right question, make sense of the answers, and thereupon make the right assumptions! If you want to be as independent and broadly informed as possible and form your own opinion about a topic, you must actively do something about it and get your information from the right sources. So, pop the bubble by not being too lazy to find your way through the data jungle and find your answers and don’t be afraid of being trapped.

Author: Cristina Fäh

Image Source Title: https://thenextweb.com/news/facebook-grandparents-need-next-gen-social-network

References:

E. Pariser: The filter bubble: What The Internet Is Hiding From You. 2011

J. Weisberg: Bubble Trouble. Is Web personalization turning us into solipsistic twists? Slate Magazine, 10. July 2011

T.D. Krafft, M.Gamer, M.Laessing, K.A. Zweig: Filterblase geplatzt? Kaum Raum für Personalisierung bei Google-Suche zur Bundeswahl 2017, Sept. 2017

M. Feuz, M-Fuller: Personal Web searching in the age of semantic capitalism: Diagnosing the mechanisms of personalization. First Monday, Vol. 16, Number 2-7 February 2011