There is a peculiar cruelty in asking entrepreneurs and investors to produce five-year business plans while the civilisational scaffolding beneath us buckles and groans. Yet this is precisely what we continue to do—spreadsheets extending confidently into 2030, IRR calculations dancing obliviously over tectonic fractures, SWOT analyses treating systemic collapse as a line-item “threat” to be mitigated alongside “increased competition.”

The lie at the heart of modern business planning is not numerical. It is cosmological. We are still writing plans as though the world oscillates around a stable mean, as though volatility is deviation, not direction.

It isn’t.

AI can now generate a polished business plan in a few hours. Financial projections, market analysis, competitive positioning, risk matrices—all assembled with fluent confidence by systems trained on thousands of previous plans. If a machine can produce the document this easily, what does that tell us about the document’s actual epistemic value? Perhaps it tells us that the traditional business plan was always more ritual than reasoning, a formulaic performance of certainty in a world that never warranted it.

The Regime Shift Nobody Wants to Price

The social enterprise movement, impact investment, ESG frameworks, they have proved inconsequential beside the scale of transformation the twenty-first century demands. We have failed—systemically, emphatically, repeatedly. [9]

Consider the data: more than 26% of companies in the S&P Global BMI generated unpriced environmental costs larger than their net income. [13] They appear profitable only by smearing their liabilities across the lungs, soils, and futures of people they will never meet. [9]

This is not a market inefficiency. It is a civilisational accounting fraud.

And into this chasm, we continue to toss business plans premised on stable throughput, cheap energy, predictable logistics, and insurable shocks. The category error is staggering.

Enter: Degenerative Volatility

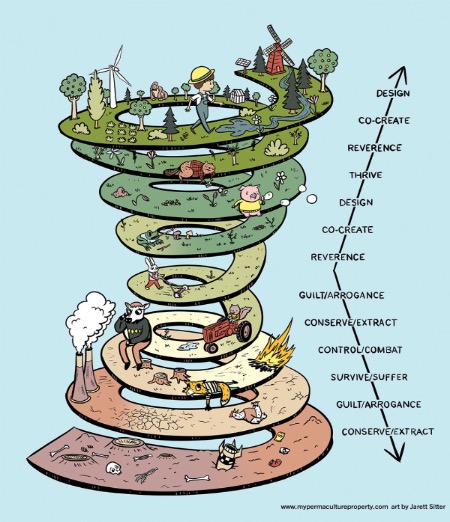

Climate commentators still speak of volatility as if the system oscillates around a recognisable mean. But the baseline itself is falling away. We have entered degenerative volatility: a condition where each downward spike ratchets the floor lower, eroding the very stability on which markets, contracts, and governance once relied. [3, 9]

At 1.7–1.9°C of warming, we lose a major global food basket. At 3°C, we trigger feedbacks no model can meaningfully bound. Price whiplash follows, amplifying inequality; inequality severs the social contract; without a social contract, there are no tradeable assets, because asset ownership is nothing more than a collective hallucination about the future. [9]

The traditional business plan is built for a world that oscillates. What happens when the oscillation becomes a descent?

The financial philosopher Elie Ayache offers a more radical proposition than the familiar Black Swan of unpredictable events. Where Nassim Taleb counsels robustness against shocks we cannot foresee, Ayache’s Blank Swan reimagines the market itself as a writing surface—not a space of prediction but of inscription, where reality is continuously authored in the moment of trading. [1] The business plan, in this frame, is not a forecast but a form of writing: you are not predicting the future but participating in its creation. The question shifts from “what will happen?” to “what are we capable of inscribing?”

The Bankruptcy of Sequential Strategy

Strategy often comforts itself with the logic of sequence. The story goes something like this: first we fix the present, then we turn to the future, and once stability is achieved, we can situate ourselves in the larger world. [8]

This story is a lullaby for the intellectually exhausted.

People do not suspend judgment until the future arrives. They evaluate every decision in real time, against the totality of their experience. An action taken “for now” is never only judged by its immediate effects, it is simultaneously read as a signal about what futures are being enabled or foreclosed, and whether past harms are being redressed or ignored. [8]

Sequential strategy therefore produces an illusion of progress. It appears orderly, but it quietly erodes legitimacy, because while institutions focus on “fixing now,” people are living in a simultaneity of horizons. [8]

Strategy must multi-solve. Every action must carry meaning across past, present, future, and mission at once. This is not poetry. It is the minimum condition of coherence in entangled times. [8]

Yet open any MBA-approved business plan template. Where is the multi-horizon architecture? Where is the acknowledgment that you are not simply projecting revenue but constructing a relationship with legitimacy?

The Factorial Repricing Nobody Has Budgeted

As we enter 2026, we face a regime shift in enterprise viability. A large share of modern corporate performance has been sustained by systematically externalising social and biophysical costs, pushing them into communities, public systems, and the ecological substrate. That externalisation is now ending. The costs that were deferred are no longer deferrable. [5]

Consider the vectors:

- Insurance retreat: Carriers are withdrawing from entire geographies and asset classes (State Farm/Allstate exiting California, Farmers leaving Florida, Lloyd’s repricing globally)

- Regulatory tightening: EU Deforestation Regulation, CSRD compliance, Scope 3 accountability.

- Supply chain weaponisation: Geopolitical fracture turning logistics into strategic vulnerability (China’s 60% rare earth / 80% battery dominance, European gas crisis)

- Demand shocks: As affordability crises cascade through consumer populations (UK grocery inflation at 19%, plant-based meat collapsing 14%, Gen Z alcohol decline)

- Refinancing walls: Debt instruments priced under old assumptions meeting reality (Low-interest debt from the growth era is expiring, forcing wineries to take on expensive new loans that their current, shrinking cash flows can no longer support)

Once failures begin, they propagate. Supplier collapse becomes production disruption; insurance withdrawal turns operating risk into non-viability; credit tightening triggers refinancing walls; demand shocks become cash-flow crises. The system moves from “bankruptcies” to “clusters,” from “downturn” to “cascade.” [5]

We face one of the largest periods of enterprise failure in modern history—an extinction-level churn for large segments of the industrial corporate form, especially those built on stable throughput, low-cost labour, cheap energy, and externalised risk. [5]

The question is not whether your business plan accounts for these dynamics. The question is whether your business plan even operates in the same ontological universe as these dynamics.

The Mission-Oriented Counter-Move: From Correction to Creation

If the diagnosis is collapse of the planning paradigm, what might replace it? The role of the state and by extension, the purpose of enterprise—must shift from fixing market failures to shaping markets around societal missions. [10, 11]

The distinction is not semantic. It is structural.

Traditional finance operates on the assumption that the private sector creates value and takes risk, while government merely provides security and facilitates work. But the public sector has been the primary risk-taker in virtually every major technological revolution, from the internet to mRNA vaccines. Private actors then capture returns that were socialised in their creation. [11]

For business planning, this implies a fundamental reorientation. If the state is re-assuming its entrepreneurial role and if the costs of externalisation are being forced back onto private balance sheets then the entire risk-return calculus shifts.

Mission-oriented business plans don’t ask “how do we capture value?” They ask: “how do we create value that aligns with the direction of travel of public investment, regulatory evolution, and civilisational need?” [10, 11]

This is not idealism. It is fiduciary realism in a regime-shifting economy.

Dynamic Capabilities and Deep Uncertainty

There is a crucial distinction between risk, which is calculable and manageable through traditional tools and deep uncertainty, which is ubiquitous in the innovation economy and requires entirely different organisational muscles. [15]

Ordinary capabilities—the proficient employment of a firm’s resources, processes, and administrative systems—are by definition unable to help the organisation respond creatively to volatility and surprises. They allow an enterprise to finish defined tasks. They won’t allow it to survive a regime shift. [15]

Dynamic capabilities, by contrast, involve sensing, seizing, and transforming—the capacity to reconfigure resources, identities, and business models in response to changing environments. Strong dynamic capabilities are essential when firms face deep uncertainty, which they frequently do in interdependent economies experiencing rapid technological change and financial disruption. [15]

Here is the planning implication: the traditional business plan is a document optimised for ordinary capabilities. It assumes stable context and measurable risk. What we need instead is a plan for transformation—a living architecture for adaptive capacity.

This is precisely where AI-generated business plans reveal their limitations. An AI can extrapolate from historical patterns with impressive fluency. It can model scenarios, stress-test assumptions, generate sensitivity analyses across dozens of variables. What it cannot do is exercise judgment under genuine novelty, the kind of novelty where the patterns themselves are breaking down. AI is trained on the past; deep uncertainty is, by definition, what the past cannot teach us.

The Architecture of Optionality: Planning for What You Cannot Know

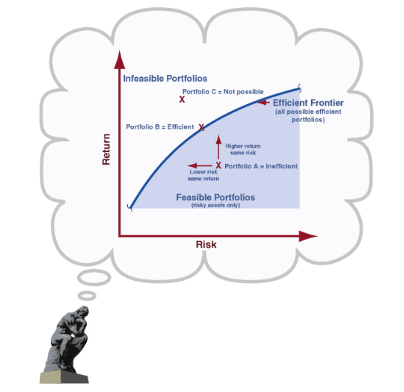

If there is a single concept that bridges systemic critique and mission-oriented alternatives, it is optionality—the deliberate cultivation of future choices that increase in value precisely as uncertainty intensifies.

Traditional business planning is allergic to optionality. Every dollar not committed to a specified use is seen as inefficiency. Every fork in the road not pre-decided is a failure of strategic clarity. The entire apparatus of IRR, NPV, and DCF assumes you can project cash flows into a future that will behave like a better-behaved version of the past.

Expanding the Possibility Space

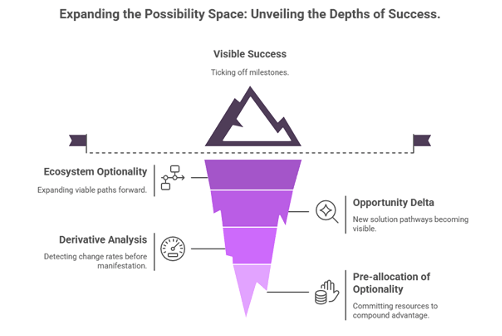

What we need is portfolio logic—multiple experiments, varied time horizons, staged bets whose feedback loops re-inform the portfolio in real time. [4]

And here is the key insight: The unit of success is not whether a milestone was ticked off, but whether the ecosystem’s optionality expanded. [4] Success is not hitting your targets. Success is having more viable paths forward than you did before.

Consider measuring “opportunity delta”: how many new solution pathways became visible because you chose not to over-specify upfront. [4] This inverts conventional wisdom, which treats specificity as rigour and open-endedness as vagueness. Under degenerative volatility, the opposite is true: over-commitment is fragility.

Leading analysis should function as a derivative term in a control system—detecting change rates before they fully manifest in situational metrics. This enables the pre-allocation of optionality: committing resources in ways that compound advantage before the inflection arrives. [7]

And perhaps most provocatively: volatility is lowered by optionality, not autarky. [6] The instinct under threat is to hoard, to build walls, to secure supply. But fortress strategies are brittle. They assume you know which resources will be scarce. In a regime-shifting world, the resource that matters tomorrow may not be the resource you stockpiled today.

Optionality—cooperative insurance pools, cross-border guarantees, flexible infrastructure, staged investments—lowers risk premium precisely because it preserves the ability to respond to what you could not have predicted. [6]

Real Options Theory: The Finance of Flexibility

Financial economics has a name for this: real options. Unlike financial options (which are contracts on traded securities), real options are the embedded choices within strategic investments—the option to defer, expand, contract, abandon, or switch a project based on how uncertainty resolves. [14, 16]

The mathematics are elegant. Under standard discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis, uncertainty is a problem—it widens confidence intervals and raises discount rates. Under real options analysis, uncertainty increases value—because the downside is capped (you can abandon) while the upside is uncapped (you can expand). A 50% increase in volatility can raise option value by 40% or more. [16]

Real options analysis has been deployed by oil majors to value offshore leases, by pharmaceutical companies to stage drug development, by infrastructure investors to sequence climate adaptation projects. What it reveals is that flexibility is an asset—and one that is systematically undervalued by traditional planning methods. [14, 16]

The challenge is that most business plans are written to eliminate optionality. They commit to specific products, specific timelines, specific markets. Each commitment forecloses alternatives. In stable environments, this is efficient. In degenerative volatility, it is suicidal.

Concrete Examples: Optionality Under Degenerative Volatility

What does optionality look like in practice? Here are six concrete architectures for preserving strategic choice in regime-shifting conditions:

1. Staged Land Acquisition for Regenerative Agriculture

Rather than purchasing 10,000 hectares outright for a regenerative farming operation, acquire 2,000 hectares with options to purchase adjacent parcels over five years. The option premium is your cost of flexibility. If climate shifts make the region unviable, you’ve limited exposure. If regenerative practices prove out and yield increase manifest, you exercise the options at pre-agreed prices.

2. Modular Infrastructure Design

Build processing facilities—whether for food, energy, or materials—in modular units that can be scaled up, scaled down, or repurposed. A modular biodigester can process agricultural waste today and be reconfigured for algae cultivation tomorrow. The upfront cost is higher than a single-purpose facility; the optionality value compensates. When the regulatory environment shifts (and it will), you’re not stranded with assets designed for a world that no longer exists.

3. Multi-Stakeholder Governance Structures

Instead of locking in a fixed equity structure with defined exit timelines, design investment vehicles with convertible instruments that can transform based on outcomes. A junior tranche that converts to equity if biodiversity metrics are met. A revenue-share mechanism that adjusts based on which ecosystem services prove monetisable. The structure itself becomes a portfolio of options on future states of the world.

4. Supplier Diversification as Strategic Insurance

In a world of supply chain weaponisation, single-source suppliers are catastrophic risk. But diversification alone is insufficient—you need activated relationships with multiple suppliers, even if you’re not currently purchasing from all of them. This means paying for optionality: maintaining smaller contracts, investing in supplier development, participating in industry consortia. The cost is real. The value is that when your primary supplier’s region floods (or faces sanctions, or experiences civil unrest), you have warm relationships to activate.

5. Workforce Capability Portfolios

Train employees in adjacent skills beyond their current roles. A financial analyst who understands regenerative agriculture. An agronomist who can read a carbon market. Cross-training is expensive and appears inefficient in a static optimisation frame. In a dynamic frame, it’s your option to pivot. When the business model shifts (and it will), you’re not starting from zero.

6. “Ecosystem Optionality” in Nature-Based Solutions

Design nature-based climate solutions to generate multiple potential value streams, even if only some will materialise. A mangrove restoration project might generate blue carbon credits, coastal protection services, sustainable aquaculture potential, ecotourism revenue, and biodiversity credits. You don’t know which markets will mature or which regulatory frameworks will provide monetisation pathways. The project that preserves optionality across all five streams is more valuable than one optimised for any single stream—even if that single stream is “most likely.”

The Opportunity Delta Metric

The provocation to measure “opportunity delta” deserves operationalisation. [4] Here’s a concrete approach:

At each strategic review, ask: How many viable pathways forward does this business have compared to twelve months ago? Not revenue. Not market share. Not even customer count. How many options for value creation exist that did not exist before?

This requires:

- Mapping adjacent possibilities: What new markets, products, partnerships, or operating models have become accessible?

- Tracking closed doors: What options have we foreclosed through our commitments?

- Valuing learning: What do we know now that we didn’t know before, and how does that knowledge expand our possibility space?

An enterprise with growing opportunity delta is increasing its fitness for an uncertain future. An enterprise with shrinking opportunity delta is betting increasingly heavily on a specific future—which, under degenerative volatility, is a losing bet even if you happen to guess right once or twice.

The Optionality Paradox

Here is the uncomfortable truth: optionality is expensive in the short term and invaluable in the long term. It requires capital that produces no immediate return. It requires governance structures that resist the siren call of “focus.” It requires investors who understand that preserving flexibility is not the same as lacking strategy.

Most capital structures are optimised for the opposite. Venture capital demands rapid scaling toward a single vision. Private equity demands operational efficiency. Public markets demand quarterly earnings guidance. The entire financial ecosystem pushes toward commitment.

The enterprises that survive the coming period will be those that found ways to buy optionality—through patient capital, through blended finance, through structures that value flexibility as a strategic asset rather than penalising it as inefficiency.

The philosopher Quentin Meillassoux, in his analysis of Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés, argues that the poem encodes a “Unique Number”—not a formula for prediction but a mode of engaging with radical contingency. [12] The throw of the dice does not abolish chance; it inhabits it. Perhaps what business planning requires is not better forecasting but a similar poetics of contingency: structures that do not resist uncertainty but compose with it. The plan becomes less spreadsheet than score—a notation for improvisation within constraints.

Context Design Engineering: Planning for an Agentic Economy

We are living through an explosion of agentic capacity, an epochal expansion in the number, scale, and kinds of entities able to sense, decide, and act. [2]

This shift renders obsolete the industrial conception of design as process and function engineering, which assumed stability, hierarchy, and compliance. The world no longer behaves as a machine to be optimised; it behaves as a field of interacting intelligences to be composed. [2]

What is now required is a theory and practice of context engineering—the design of relational environments that reinforce agency through presence, not control; coherence, not compliance. [2]

A context engineer does not ask “How should this system perform?” but “What should this system make possible?” Their concern is not efficiency but viability, the sustained capacity for difference, adaptation, and mutual flourishing across interdependent agents. [2]

Translate this into the language of business planning: stop planning for outcomes. Start planning for conditions. The question is not “what will our revenue be in Year 3?” The question is “what relational, material, and institutional conditions will make viable value-creation possible in the contexts we inhabit?”

The AI Paradox: When the Plan Writes Itself

Let us return to the unsettling fact that opened this essay: AI can now generate a business plan in hours. What are the implications?

Whether authored by AI or human intellect, the credibility of any five-year business plan is questionable when the future is shifting into an entirely new regime. The AI simply makes visible what was always true: the traditional business plan is a genre, a set of conventions, a ritual of confidence. The machine can perform the ritual flawlessly. That’s the problem.

AI excels at risk; it fails at uncertainty. Pattern recognition at scale is what machine learning does extraordinarily well. Give it historical data, and it will find correlations, project trends, stress-test scenarios. But this is the domain of calculable risk, not deep uncertainty. When the underlying distributions shift, when the patterns themselves are breaking down, AI has no advantage over human judgment. It may have a disadvantage: its confidence is trained on a world that is ceasing to exist.

The correct response to AI-generated plans is not to retreat into human intuition as though it were more reliable. Human judgment is riddled with biases, blind spots, and the same backward-looking tendencies that limit AI. The point is not that humans are better at predicting the future. The point is that nobody is good at predicting the future under degenerative volatility, and strategy must be redesigned around that fact.

The value shifts from the document to the process. If AI can produce the artifact in hours, then the artifact is not where the value lives. The value lives in the process that surrounds it: the conversations, the stress-testing, the stakeholder alignment, the ongoing adaptation. A plan generated in three hours and never revisited is worthless. A plan generated in three hours and subjected to rigorous participatory critique, updated quarterly, and embedded in governance structures that force assumption-checking, that might be worth something.

The proper use of AI in planning is not to produce a final document faster. It is to produce more drafts, more scenarios, more stress-tests—and to do so quickly enough that the planning process becomes genuinely adaptive. Instead of one plan laboriously crafted over months and then defended against reality, imagine dozens of plan variants generated, critiqued, and evolved in real time as conditions shift. This is portfolio logic applied to the planning process itself.

AI cannot walk a páramo and understand which watershed matters most to downstream farmers. It cannot sit in a co-design workshop and sense which stakeholders are losing trust. It cannot feel the legitimacy deficit that precedes institutional collapse. The business plans that will matter are not the ones that model reality most precisely—they are the ones embedded in relationships dense enough to navigate what no model can foresee.

What Business Plans Might Become: Twelve Provocations

If we take the systemic critique seriously, we are not merely revising the business plan—we are composting it and growing something else in its place. Here are twelve propositions for what that something else might look like:

1. Bio-regional grounding, not global abstraction. Every plan must articulate its relationship to place—materials, nutrient flows, energy sources, communities. Global scale without bio-regional rootedness is an externalisation machine.

2. Multi-horizon strategy. No plan survives contact with reality if it only addresses “now.” Build in lagging (where we’ve been), situational (where we are), leading (where we’re going), and universal (non-negotiables) registers. [7]

3. Legitimacy as an asset class. The capacity of strangers to reason together—to trust your enterprise—is not a marketing problem. It is a structural condition of value creation. Measure it. Invest in it. Lose it at your peril. [9]

4. Full-cost accounting. If your margin depends on externalising costs to communities, ecosystems, or future generations, you do not have a margin. You have a liability in disguise. [5]

5. Mission orientation. Align your enterprise with the direction of travel of public investment and civilisational need. Not because it’s virtuous but because that’s where durable demand and regulatory tailwind will live. [10, 11]

6. Insurance as strategic intelligence. Track what insurers are pricing in. Their models are among the most sophisticated early-warning systems for regime shifts. When they withdraw, you are seeing the future. [5]

7. Dynamic capabilities over static projections. The plan should describe your capacity to sense, seize, and transform, not just your forecast for next quarter. In regimes of deep uncertainty, adaptability is the only robust asset. [15]

8. Blended capital architecture. Patient funds, catalytic private bets, community investment, regenerative returns. Learn to straddle infrastructure and community, not just optimise for one metric. [9, 11]

9. Regenerative value design. Don’t just extract value from inputs. Ask what you are regenerating: soils, relationships, skills, ecosystems. The twenty-first-century blue chips are not financial; they are relational and ecological. [9]

10. Plans as living documents. A plan that is not regularly stress-tested, updated, and ritually challenged is not a plan. It is a relic. Build in pre-mortems, assumption kill-lists, scenario inversions—as part of governance hygiene. [7]

11. Optionality as a core metric. Measure opportunity delta: how many viable pathways forward does the enterprise have compared to last year? Preserve flexibility through staged investments, modular infrastructure, convertible instruments, and multi-stakeholder structures. Treat premature commitment as a form of risk, not rigour. [4, 14]

12. Portfolio logic over project logic. Replace the critical-path mindset with portfolio thinking. Multiple experiments, varied time horizons, staged bets with feedback loops. The unit of success is not whether a milestone was ticked off, but whether the ecosystem’s optionality expanded. [4]

The Practitioners’ Bind

None of this is easy. Investors want tidy spreadsheets. Banks want collateral. Regulators want compliance. No one rewards you for saying “the baseline is collapsing and we’re building adaptive capacity for a world we cannot fully predict.”

And yet.

The practitioners who move first, who build enterprises designed for viability under constraint, who stop externalising and start regenerating, who think in centuries rather than quarters, will be the ones standing when the dust settles. The others will be on the wrong side of the largest period of enterprise failure in modern history. [5]

The choice is not between idealism and realism. The choice is between legacy assumptions and systemic literacy.

A Personal Reflection: The Finance Architecture We’re Actually Building

I use AI daily to draft financial models, generate scenario analyses, stress-test assumptions, synthesise research. It accelerates everything. But here is what I’ve learned: the faster I can produce a plan, the more time I have for the work that matters—the conversations, the negotiations, the co-design sessions. AI handles the formulaic; humans handle the relational. The danger is confusing the two—believing that because a plan looks sophisticated, it is sophisticated. The sophistication lives in the relationships that surround the document, not in the document itself.

The biggest risk is not financial—it is paradigmatic. The investors I speak with are intelligent, well-resourced, and increasingly concerned. But many are still operating under legacy assumptions about what constitutes a viable business. The hardest conversation is not about risk-adjusted returns. It is about ontology: what kind of world are we building for, and does our capital structure reflect that world?

But here is my conviction: the business plans that will matter in 2030 are being written now by people who understand that we are not optimising a stable system. We are designing for transformation under constraint.

That requires a different kind of courage to build institutions we may not live to see mature, to price assets that don’t yet exist in market ontologies, to hold complexity without collapsing into cynicism, and to value the preservation of future options as highly as we value present returns.

What some call inventive seriousness and others call mission orientation; I call the only game worth playing.

The business plan, as we knew it, is dead. What rises in its place will determine whether we have enterprises—or a civilisation—worth passing on. And if they are worth passing on, they become something else entirely: not disposable instruments but rich texts, artifacts that future generations might still decipher, cultivate, and build upon—the way we still read Mallarmé, searching for numbers hidden in the dice.

This piece was written for entrepreneurs, investors, and policymakers who suspect that the tools they’ve been given are insufficient to the moment. It is offered not as a complete answer but as an invitation to think together—with the rigor, humility, and urgency the moment demands.

Written by Marina Skorulskaja using Anthropic. (2026). Claude Opus 4.5 (January 13 version) [Large language model]. https://claude.ai

References

[1] Ayache, E. (2010). The Blank Swan: The End of Probability. Wiley.

[2] Johar, I. (2025). “Context Design Engineering.” Indy Johar Substack.

[3] Johar, I. (2025). “Degenerative Volatility: Living on a Sinking Platform.” Indy Johar Substack.

[4] Johar, I. (2025). “Engineering Futures: Three Shifts We Can’t Postpone.” Indy Johar Substack.

[5] Johar, I. (2025). “Facing into Systemic Enterprise Collapse Risks (2026+)—with the Industrial Welfarism Layer.” Indy Johar Substack.

[6] Johar, I. (2025). “Money as a Claim on Future Energy.” Indy Johar Substack.

[7] Johar, I. (2025). “Situating Analysis.” Indy Johar Substack.

[8] Johar, I. (2025). “The Necessity for Strategy to Multi-Solve.” Indy Johar Substack.

[9] Johar, I. (2025). “We Have Failed—Now Let’s Get Serious.” Indy Johar Substack.

[10] Mazzucato, M. (2025). “Directing Growth: How Mission-Oriented Industrial Strategy Drives Productivity.” UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose Working Paper.

[11] Mazzucato, M. (2021). Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism. Penguin.

[12] Meillassoux, Q. (2012). The Number and the Siren: A Decipherment of Mallarmé’s Coup de Dés. Urbanomic/Sequence Press.

[13] S&P Global. (2023). “The Big Picture: Unpriced Environmental Costs.” S&P Global Sustainable1.

[14] Smit, H. (2025). “Sustainability Real Options.” California Management Review.

[15] Teece, D., Peteraf, M., & Leih, S. (2016). “Dynamic Capabilities and Organizational Agility: Risk, Uncertainty, and Strategy in the Innovation Economy.” California Management Review 58(4), 13-35.

[16] Trigeorgis, L. & Schwartz, E. (2000). Real Options and Investment under Uncertainty: Classical Readings and Recent Contributions. MIT Press.